This is the first part of a series of kinship essays that will turn into a book called Kin & Caliber.

Table of Contents

- Why Kinship?

- Blood from a Stone: The First Kinship

- Local Totemism

- Matrilineal Descent

- Matrilocal Marriage

- Patrilineal Descent

- Patrilocal Marriage and the City

- Rethinking Ancient Kinship

- Iron

- Gunpowder and Bilateral Descent

- The Atomic and Alineal Descent

Why Kinship?

In 2018, I was doing a lot of personal Biblical scholarship in my spare time. I followed the parashah system, which cycles through the entire Torah—the first 5 books of the Bible—every year. But whenever I came to Genesis 12, the scene where Abraham takes his wife—and “half-sister”—Sarah to Egypt and tells her to pretend they weren’t married, it would always hit me by surprise. Pharaoh marries her, gets an STD or something, gets angry at Abraham for deceiving him, and sends him off with Sarah and a bunch of loot. Why would Abraham do such a thing? Why did he marry his half-sister anyway? Is any of this model “Biblical behavior?” The story makes little sense, and in discussing it with other Bible students, I’ve found that apologists will twist themselves into strange knots to explain what the story means, even when those explanations defy reason. A common explanation is that the anti-incest laws had not been given in Abraham’s time, as they don’t come until Leviticus, generations later, after the Exodus from Egypt. But every society, even the “lowest” according to the Victorians, tabooed certain marriages as incestuous. It’s simply impossible for me to imagine there was ever a time when marrying one’s sister was legal1.

At the time, I was also reading James G. Frazer’s 12-volume The Golden Bough, which served as a field guide to anthropology and provided much-needed context for biblical laws regarding tithing, new moons, blood payment, and numerous other ancient customs. The Golden Bough volume Spirits of the Corn and the Wild, parts 1 and 2, alone is about first-fruits celebrations and contains 700 pages of field data of European, African, Australian, Indian, Asian, and North American first-fruits festivals. After reading this, you will most likely understand first fruits better than your pastor or priest, and likely find their explanations very baffling, even modernist.

Another reason I was studying anthropology on the side is I wanted to understand the family dynamics of the Bible, especially those of Genesis, which is laden with complex marriages that strain our modern sentiments: Abraham marrying his half-sister, Isaac marrying his cousin, Jacob marrying 2 of his cousins in a sororate marriage (where a man marries two sisters, as was done in many Native North American tribes), Judah’s sons being punished with death for not keeping the levirate marriage (where a man dies and his younger brother marries his widow to keep his line going), Joseph marrying the daughter of an Egyptian high priest, Moses’ father marrying his aunt, and so on. None of these seems legitimate in our modern notions of kinship, but I had a feeling there was much more to them than what was indicated in the plain English text.

For kinship studies, I first delved into Frazer’s Totemism and Exogamy, my first foray into kinship. I then expanded into other Scottish Enlightenment types, such as W. Robertson Smith’s Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia (1903), Lewis Morgan’s Ancient Society (1877), and others. These authors shed important light on a problem that plagued kinship studies before the 19th century, when one could accuse the Europeans of oversimplifying the subject. A Christian missionary or anthropologist would go to, say, Hawaii, and ask a male villager whether Lana was his “sister.” He’d respond, “Yes, Lana is my sister (kaikua’ana / kaikaina),” and the missionary would assume this meant he and Lana shared the same mother and father. But the kaikua’ana term might also mean Lana is his female cousin. What the Europeans didn’t realize at the time was that many non-European kinship terms, such as sister, brother, mother, etc., didn’t indicate biological (or consanguineous) relationships, but rather their classificatory relationships. In the case of Hawaiian, the “sister” might not be a “sister” in our terms, but the term indicates that she is not marriageable. In many Australian and African tribes, one’s “sister” might even be a 3rd or 4th or even more distant cousin, a marriageable prospect in some Western societies, but as tabooed as a biological sister in a classificatory system.

What Is Kinship?

Difficulties in kinship terminology aside, an important question to ask is, What exactly is kinship? On an anthropological level, kinship is a nexus of one’s network of marriage (who can marry whom), inheritance (how property passes from one person to another), and vengeance (who avenges whom when they are wronged or killed). These networks give rise to various social orders, which in turn produce specific technologies, beliefs, and other cultural forms. But since I’m a stuntman and deal in the art of choreographed violence, my focus is specifically on how kinship interfaces with violence.

In my book If These Fists Could Talk: A Stuntman’s Unflinching Take on Violence (available here on Amazon), I formulate the ROBA Hypothesis on human violence. Whereas animal combat uses only their natural weapons, human combat is capable of using any object—a trait I call reciprocal, object-based aggression (ROBA). All humans are trying, and failing, to anticipate the weapons of all enemies, causing a series of nested tactics that are fundamentally recursive, and therefore apocalyptic. Human violence escalates to extremes, so we must defer it somehow.

There’s good news: this same recursion is the basis of all human culture, including language, religion, art, economics, and politics. Just as our violence escalates to extremes due to recursion, our deferential culture can escalate to extremes too, only it is productive as opposed to destructive. Culture defers ROBA. In fact, it’s simply on the other side of the coin. Or, if we think of ROBA as hot water flowing through a plumbing system, then deferential culture is the cold water.

Not all of our deferential, cultural modes arise at the same time. Modern societies have a separation of church and state; we have different forms of art, genres of music, and subgenres of those; we have language, which produced computer programming, which produced internet websites, which produced meme culture. All deferential forms appear to split off from their parent forms, as evidenced by the fact that ancient societies did not so readily differentiate these modalities. Economics and worship of the dead were wrapped up together, church and state were one, and music and dance were indistinguishable. We could make a rough family tree, but it seems clear that all societies have at least the basic cultural forms: religion, language, and art.

But there’s one cultural form that might precede these: kinship. Kinship is the inescapable cultural modality that is ever-present wherever humans exist, taking elaborate forms in even the most ancient systems. Leading thinkers in primatology, archaeology, and anthropology have repeatedly argued that human kinship is merely an extension of animal reproduction, much as human violence is an extension of animal aggression, and human language is an extension of animal communication. They hypothesize that kinship evolved to bond families together and help them survive in their environment, leading to the development of hunting groups, human sexual selection, and child-rearing practices. Of course, they negate that kinship in every ancient society was laden with religious laws, and almost all punished incest with death.

The sciences have never identified the simple difference between human and ape combat, so they can’t even posit a causal link between the two species’ forms of combat. Once one accepts the simple tenets of the ROBA Hypothesis, it becomes clear that everything humans do is, to some extent, a means to defer ROBA. Kinship, which is fully formed in every culture, is perhaps the first and most elegant solution to the ever-present threat of human violence. By creating a system of alliance and obligation through blood ties and marriage, and outlawing incestuous practices that might prevent the family’s integration into the larger network, early societies found a way to defer the apocalyptic potential of ROBA, exchanging a violent act for a peaceful one. The structure of a family, therefore, is not just a biological reality but a profoundly cultural one, a language written in relationships designed to prevent bloodshed.

Blood from a Stone: The First Kinship

The first kinship system, then, might have been intimately tied to violence, kinship and violence being the same institution. One’s blood ties determined whom one killed in vengeance, whom one married to institute bonds between families and mitigate intertribal violence—and whom one could absolutely not marry—and how clan affiliation was passed to children—which, in effect, stipulated whom they could, or were obligated to, marry.

Darwinist logic seems to stipulate that before human groups reached the Dunbar number in size of 1502, they roamed in tiny packs. Indeed, pop culture still retains the stereotype of the kinless caveman. But if humans evolved from apes, the earliest human groups would have been at least as large as those primate groups they descended from, their membership presumably numbering in the dozens. So, there’s little reason to assume that humans were ever solitary. The most ancient of societies evince large and complex groups, which are always networked through intertribal marriage. If they were ever un-networked, when and how? As we’ll see, intertribal marriage was always necessary.

Since humans are uniquely capable of ROBA, the first humans, presumably lacking any technology, would still have had access to an infinite supply of one particular weapon: rocks. Of course, sticks could potentially do the job too, but they require sharpening, fire-hardening, and a certain level of skill. Rocks required nothing except aim and gravity. Even lacking a decent throwing arm, one needed only to drop a rock from a decent height onto the victim’s head. ROBA was truly a democratic art that opened the franchise of combat to men, women, children, and even the elderly.

The potential for murder was therefore everywhere, and if any person were murdered, ancient laws typically stipulated that the victim’s family could demand blood payment from any person of the offender’s clan, since clans were united under a single “blood.” The murderer himself might get off free, while someone else from his tribe paid his blood debt. But blood payment could never bring about a true balance of justice. One side would inevitably hold a grudge against the other until blood was drawn again, continuing the cycle. Once the two families engaged in a game of mutual blood vendetta for long enough, all people involved would risk extermination, so apocalyptic violence is.

Intertribal marriage was a resolution to the issue of blood vengeance. By forcing every member to marry outside their clan marker into the opposing tribe—a practice called “exogamy”—the two tribes created a natural brake against violence. Since Tribe A intermarried with Tribe B, all households had at least one member of A and one member of B. If Tribe A went to war against Tribe B, then all marriages would potentially be torn apart. Intertribal marriage, and its corollary taboo against incest, ensured the two tribes would keep the peace.

Which came first? Murderous warfare? Or intertribal marriage and the incest taboo? Robin Fox in The Red Lamp of Incest claims that the incest taboo came first from a gradual evolution of the size of the protohuman amygdala, which made incest seem more and more disgusting and was therefore selected against. We might assume the same disgust led to the rise of certain cooking practices that gradually eliminated bitter flavors in favor of savory ones. If a person serves a disgusting dish, they get a scowl. But if a person marries a disgusting person—a tabooed, unmarriageable kin, even if the union is consensual—the penalty is death. Even theft and rape are treated with more leniency than incest. And this is the case in practically all ancient societies. So far, there is no satisfactory Darwinist explanation for this particular harshness. But the ROBA explanation is simple: incest taboos ensure families exchange marriage partners to facilitate intertribal unions, which defers ROBA. One could say that kinship is the first self-defense technique3.

This seems like a chicken-or-egg problem: ROBA necessitated intermarriage and the incest taboo, while intermarriage and the incest taboo prevented ROBA. Perhaps this first instance of kinship can only be hypothetical. Where it came from, we need not hypothesize. We are only concerned with kinship itself and its relationship with ROBA.

Now that we’ve laid the foundation for kinship according to ROBA, a Ground Zero, we can move to the next stage of kinship.

Local Totemism

Frazer claimed in Totemism that, in the earliest human societies, paternity was unknown. We might—and, I believe, we should—assume that marriage was an institution at this point4. When the man slept with the woman, she became pregnant, but she didn’t know she was pregnant for about a month. When the woman felt the first quickening in the womb, her people assumed she had been impregnated at that same moment. If she felt the quickening at Snake Watering Hole, then she had been impregnated by the Snake god. If at Big Rock, then by the Big Rock god. If in the rain, then by the Rain god. The child was given the totem marker of that god: Snake, Big Rock, Rain, etc.

The totem marker was more than a mascot: it determined whom one could marry5. Because the totem was a local landmark or some natural flora or fauna, Frazer called this “local Totemism”6. Snakes could not marry Snakes, Big Rocks could not marry Big Rocks, and often the specific locality of the totem ensured that they represented geographically disparate groups. There might be many generations of Snakes, and some of them may be distant cousins to one another, but the marriage prohibition stood: these were termed brothers and sisters, and they did not marry.

Instead, exogamy was the rule. One must marry out. A Snake was required to marry a Rain, and a Rain required to marry a Snake, which was essentially an exchange of grooms between the different clans7. Claude Lévi-Strauss (CLS) called this “Restricted Exchange.” Or a Snake would “buy” a Rain marriage partner, a Rain would “buy” a Big Rock marriage partner, and a Big Rock would “buy” a Snake marriage partner, producing a circular dependency where people flowed one way along the cycle, payments—”prestations”—flowing the other way. The Kachin of Burma had a 5-class general exchange system. If any party reneged on one of dozens of different prestations demanded at various points in the marriage process, there were heavy penalties because this disrupted the entire cycle of exchange. CLS called this “Generalized Exchange.”

Matrilineal Descent

Frazer then outlined a second stage of social development, in which paternity may or may not have been known, but regardless, the child inherited the totem marker of the mother by default. This is the basis of “matrilineal descent”8. The law of exogamy still held, as did the incest taboo: Snakes could not intra-marry with other Snakes, Big Rocks could not intra-marry with Big Rocks, but must inter-marry with other totem markers. Intra-marriage was considered incest and was often punishable by death.

(These days, many claim that such incest taboos evolved as a way to protect against birth defects, but CLS makes a compelling counterargument in The Elementary Structures of Kinship. The odds of birth defects among siblings were still very low even in first-cousin marriage societies, and it would have taken dozens, perhaps hundreds, of generations for tribes to notice such defects emerge after multiple sibling marriages.

Even in connection with recessive characteristics arising from mutation within a given population, Dahlberg estimates that the role of consanguineous marriages in the production of homozygotes is very slight, because for every homozygote from a consanguineous marriage, there are an enormous number of heterozygotes which, if the population is sufficiently small, will necessarily reproduce among themselves. Hence, in a population of eighty, the prohibition of marriage between near relatives, including first cousins, would only reduce the carriers of rare recessive characteristics by 10 per cent to 15 per cent. These considerations are important since they introduce the quantitative notion of population size. The economic systems of some primitive or archaic societies severely limit population size, and it is precisely for a population of such a size that the regulation of consanguineous marriages can have only negligible genetic consequences. Without fully attacking the problem to which modern theoreticians can only hazard provisional and highly varied solutions,^ it can therefore be seen that primitive mankind was not in a demographic position which would even have permitted him to ascertain the facts of the matter.

Claude Levi-Strauss, Elementary Structures of Kinship, p. 16

And what defects would they have guarded against, exactly? A visible birth defect could be detected early on and be cause for infanticide or abandonment, but the modern notion of “low IQ inbreeding” would not have occurred to native society, not for dozens of generations anyway. And what exactly did IQ mean to them? Was intuition—the so-called Emotional Intelligence Quotient of today’s social sciences—not a more crucial social skill? High IQ might have appeared even stranger than low IQ, if only because higher IQ individuals tend to isolate and focus on singular tasks, something anathema to tribal life. My ROBA Hypothesis sees this as a moot point: human societies would have always been populous. If we accept that humans evolved from primate societies, then there would have been 20+ members at the beginning, and marriage would have compounded this. Therefore, the myth of the wandering caveman has no basis, and there would have been only occasional cases of siblings marrying. In almost all instances, the male leaves the family to go intermarry with a foreigner, however distant, and the family expects a groom or payment in return, because they need to marry their daughter off, or buy a groom themselves.

For our purposes, the child inheriting the totem from the mother is less important than the configuration of the marriage. Under all reported systems of matrilineal descent, the husband migrates from his tribe into the wife’s tribe, where he lives as a foreigner. The wife’s family may pay for his labor9, or the husband will be paid a percentage of his economic output. Some agreement is made, but the direction is the same: the husband moves to the wife’s home. This is the basis of matrilocal marriage.

Matrilocal Marriage

Under matrilocal marriage, there is a network of exchanges: Snake husbands going to Rain wives’ homes, gifts/pretestations going to the Snake tribe, while at the same time Rain husbands going to Snake wives’ homes and gifts going to the Rain tribe. More tribes can intermarry into this network for mutual defense, and the network becomes wider. Lewis Morgan chronicled many Native American tribes with 10–22 such intermarrying tribes, forming a vast network of alliances.

Let’s pause for a moment and discuss the implications of a wide, matrilineal marriage network. First, such a network provides a means of vengeance. If anyone wrongs you, you can expect someone in your network to avenge the wrong, seeking payment in blood or some goods. If your network covers hundreds of square miles, you have a broad right of passage. Second, intertribal warfare in the networks sends shocks and reverberations through all its marriages. Let’s say there’s this marriage configuration: Snake woman marries Wolf man, Wolf woman marries Rain man, and Rain woman marries Cactus man. If Snake and Cactus go to war, then Wolf might be expected to ally with their Snake marriage partners, but they are also intermarried into Rain, who is intermarried into Cactus. Wolf and Rain marriages threaten to be torn apart by the warfare. Intertribal, matrilocal marriage is effectively a stopgap against intertribal warfare. Lewis Morgan’s Ancient Society details how the Iroquois five-tribe Confederacy required every tribe to have all other totems intermarry within it10.

Another byproduct of matrilocal society is a wide array of dialects. When men are constantly moving from their homes into their wives’ homes, they bring foreign dialects with them. And then their wives’ sons, who adopt the local tongue, will move and do the same. And so on. The network effect of matrilocal marriage is a wide dispersal of dialects. Spencer and Gillen wrote about how some Australian Aborigines could speak a dozen dialects. Frazer’s Anthologia Anthropologica details “wife’s tongue” in Bantu societies, where women are tabooed from speaking words that sound like their husbands’ names, forcing them to create slang or new circumlocutions, and producing a very fluid linguistic state. One can expect to be fluent in a dozen dialects in matrilocal networks, but the fluid state of the languages also seems to prevent a written language from forming. Authors like Leonard Shlain (The Alphabet Versus the Goddess) claim that written language “evolves” from spoken language, but he and most linguists negate the impact of kinship on this phenomenon. In reality, there’s no chance that written language can be sustained without widespread patrilocal marriage, which we’ll cover later.

Another product of matrilocal networks is the dispersion of culture throughout the network. The male not only brings his dialect to his wife’s village, but also his rites, totem, taboos, and other customs. Just as matrilocal networks disperse languages, they also disperse religions, creating the vast pantheons of polytheistic society. Shlain attributes the onset of monotheism to the emergence of the patriarchy, but this is only partially correct: patrilineal descent is not adequate to knock down all the other gods to enshrine a single, monotheistic god. Patrilocal marriage is the necessary component. Until then, societies are de facto polytheistic11.

A fourth implication of matrilocal marriage is that inheritance and wealth have to be physically transportable. Under matrilineal descent, fathers do not give their wealth to their biological children, but to their sisters’ biological children. Recall that husbands migrate to their wives’ tribes under matrilocal marriage. Whatever wealth they acquire in their foreign land must be transportable back to their sisters’ land, or else it comes under the ownership of the wife’s tribe. If his heirs are nearby, the wealth might include large herd animals, sacks of grain, etc. But if the heirs are far away, the wealth may only be a few spears, some skins, medicines, and non-tangibles like dances and songs.

Regardless of how far away his heirs live, men in a matrilocal society cannot bequeath buildings or walls. If a man builds a shelter or a fortification in his wife’s village, his wife’s village owns it. He might be commissioned for this work, but he has no personal ownership over his work and no incentive to do it beyond payment. Additionally, the wide network of intertribal, matrilocal marriages tends to ensure massive warfare never happens anyway. Castles, fortifications, moats, and other works are only necessary when warfare is destructive, but Stone Age warfare tends to be a warfare of raids and retribution, which elders can mitigate through the usual gears of tribal politics12. As we’ll see, the advent of iron warfare weakened this system. It necessitated the construction of large-scale fortifications, and gunpowder was the final nail in the coffin for matrilocal marriage networks.

One more implication is that public land in matrilocal networks tends to be held in a communal trust, overseen by an elders system—typically males, even in matrilineal societies—which decides fishing, hunting, and grazing rights, as well as lodge construction. Private property passes down through the maternal line. In early 2025, I visited a Navajo hogan in Gallup, and the owner was a Navajo woman, whose Muskogee husband had migrated to her homestead from Mississippi, as per their shared matrilocal customs. Her family owned dozens of square miles of land in the area, all of which had passed through the female line for generations. To this day, the Navajo are primarily matrilocal.

One final implication of matrilocal networks is technological in nature. Because there is a constant flow of males from one tribe to another, there is little (if any) opportunity, incentive, or need to engage in long-term public works projects like mining or large-scale agriculture. Jared Diamond argued in Guns, Germs, and Steel that agriculture (and associated functions like domestication) evolved when hunter-gatherers settled down. Why would they settle down? Because, according to Diamond, it outcompetes the hunter-gatherer lifestyle:

Suppose that North American wild apples really would have evolved into a terrific crop if only Indian hunter-gatherers had settled down and cultivated them. But nomadic hunter-gatherers would not throw over their traditional way of life, settle in villages, and start tending apple orchards unless many other domesticable wild plants and animals were available to make a sedentary food-producing existence competitive with a hunting-gathering existence. (p. 134)

My argument here is that Diamond is missing a crucial step: nomadic hunter-gatherers can’t even begin to lead a “sedentary food-producing existence” until their kinship networks are configured for it, meaning they must transition from matrilocal to patrilocal marriage. Such a shift is not made overnight. In fact, it’s practically catastrophic to the culture in question. We’ll discuss why later.

(Diamond, like Shlain, never mentions kinship once in Guns. Perhaps this is because, like most post-war anthropology, the idea that kinship might be the prime driver behind innovation or “progress” smacks of racism in the Western, Democratic mind. It implies that one’s family or caste restricts them from “advancing” from barbarism to civilization, or from tribal life to city life. There are three problems with this. 1) Kinship is not static because crises—acts of God, force majeure—trigger major shifts in kinship; 2) the globalism and mass media political program that took over after WWII, and solidified around 1999, produced a crisis steady-state where kinship networks were being constantly reconfigured at a breakneck pace; 3) the city-dwelling anthropologist must examine their own biases about what “progress” means, because the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that city-living, or even suburban-living, was not the utopian lifestyle we were raised to believe. The remote work movement meant a flight out of cities into smaller, cheaper towns around the country—even around the world, thanks to fast internet speeds—which is as much “progress” as was moving from the small town to the city to begin with.)

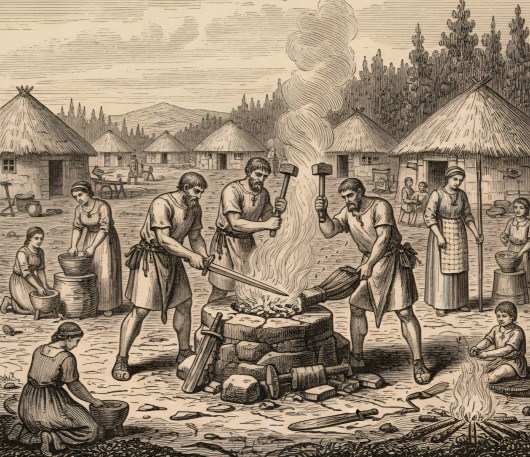

And just like agriculture, mining requires a significant shift in kinship configuration. To really do mining, one must assert ownership over an entire mountain, invest generations of labor into mining operations, get the fires hot enough to smelt the stuff out of the quarry—easy for gold, harder for copper, very difficult for iron—and have generations of artisans who can cast it. Almost all iron smelting was done around the Fertile Crescent, with some spots in Thailand and China. There was no iron smelting anywhere in the Americas, and the only people who could make bronze were the Incas, who, not coincidentally, had a patrilocal marriage system. It’s the same pattern the world over. Matrilocal marriage creates a wide, flat network of defense and wisdom, while patrilocal marriage creates nuclear enclaves of defense and wisdom. The two cannot intermarry. We’ll see why later.

We can see how the concept of “wealth” differs significantly in matrilocal networks. It lies not in one’s estate, but in one’s relationships, customs, independence, and agency. Such a wide network gives way to broadened hunting and gathering and slash-and-burn rights, fewer feuds and wars, vaster dialects and pantheons (almost always without writing), and basically no metallurgy. We tend to find that matrilocal networks—with the exception of the Aztecs, who were arguably transitioning into patrilocality like the Incas—are effectively in the Neolithic Stone Age.

Patrilineal Descent

Frazer claimed that patrilineal descent was the next stage of civilization after the matrilineal, but this need not necessarily be true. We can draw up any number of exceptions. Perhaps the first man to move to his wife’s home was a chief, but he need not have accepted the matrilineal descent model. Perhaps he had enough power to demand ownership over his biological children. Perhaps that was his payment for moving in the first place. But perhaps his nepotism spread sclerosis across the matrilocal marriage network and was overpowered by the wives’ families. Perhaps matrilineal descent took hold afterward. We can’t know the timeline for sure.

On the other hand, we must also avoid the error of Henry Sumner Maine, who assumed that patrilineal descent was the original kinship system in his Ancient Law. He seemed to believe that the Roman system of Patria potestas—the patriarchal power of life and death, the same as Confucianism in China—stemmed from the original patriarchal system outlined in Genesis chapters 4–5, which summarizes the patrilineal lineages ending in Noah and his sons Shem, Ham, and Japheth. Maine believed these men fathered all the nations and, since their wives are unnamed, he assumed they also operated under Patria potestas13. John McLennan’s The Patriarchal Theory makes the opposite case, claiming that matrilineal descent always came first. Whether this is always true is, again, debatable, but it seems more common than the patrilineal coming first.

Let’s assume matrilineal descent did come first, and use the Snake clan as our base. Rain men move in to marry and live with their Snake wives. Perhaps there are thirty of these Rain men in Snake territory, all speaking their own language, doing their own rites, telling their own water cooler jokes. They might build a lodge, a kind of Rain embassy, where they can do all these things. They have their own Rain cultural enclave. They might also decide to raid a distant tribe—say, Crow—and bring back booty. The Snake elders don’t oppose this, so long as the Rain men share the booty. So they raid Crow, kill some of the men and children, and bring back livestock, skins, weapons, and Crow women into Snake territory. The Crow women, now widows, are now at the disposal of Rain men. A percentage of them might go to Snake men. And we might assume that, as was the case in many Native American tribes, Rain men were often polygamous. The Crow women are now “captive brides”14. The Rain men sleep with them and produce offspring. Whose property are they? Under matrilineal law, the children are Crow. But why wouldn’t the Rain men assert ownership over these children? The Snake elders may oppose them—it would be a violation of local custom—but the Rain men have proven to be effective and dangerous raiders. Perhaps the Snake elders make a deal with them: their captive brides’ sons can be adopted as Rain children, the daughters Snake children, but the sons cannot marry Snakes. Or they are forced to move immediately to Rain territory. Or some such deal.

In short, this is one of various ways that patrilineal descent could emerge as its own kinship enclave within a matrilineal network. But these male children of captive brides, though they are Rain boys, if they are allowed to stay and marry Snake women, their children will be Snake children. And so long as inheritance still operates the same way—men always transporting wealth over a distance to their sisters’ children—these men will still have no incentive to build an estate, fortification, or a mine for their progeny because property must be transportable, and these assets are not. The children of the Crow captive brides may even carry on their own patrilineal system. There are many such cases where patrilineal and matrilineal tribes intermarry, as among the Apache and Southern Indian tribes. This difference might produce a spiraling structure, which could gradually crystallize into a caste system; however, intermarriage remains the rule for securing intertribal peace. It’s only when a tribe transitions to patrilocal marriage that intermarriage within the network is no longer possible.

Patrilocal Marriage (PLM) and the City

A shift from matrilocal to patrilocal marriage creates a sea change in social structure. Not only do patrilocal children inherit the clan marker of the biological father, but the male heirs also inherit his entire estate. This is the recipe for building a city, but there’s one problem: patrilocal people cannot intermarry with matrilocal people, not without a lot of trouble anyway. I’ll explain why.

To recap, under matrilocal rules, a Snake male leaves the Snake village to live with his Rain wife in Rain village as a foreigner. Adulthood being the productive years of his life, he amasses his own property, which he then bequeaths to his biological sisters’ children back at the Snake village. Similarly, Rain males move to Snake territory and bequeath their property to their sisters’ children at the Rain village. Property must be easily transportable, and all these incentives result in a smaller bulk of inheritance, none of which is fortifications, forges, graves, or walls. Both Snake and Rain clans are satisfied with this arrangement because all people are receiving inheritance from their respective out-of-town maternal uncles.

A man might not marry, remaining in his hometown, acting as a “father” for his sisters’ children, whom he also calls his “sons” and “daughters,” and his inheritance can be bequeathed locally to them. This is an opportunity for him to build an estate, but typically, only the most productive men are married off because they add value to their wives’ tribes. An unproductive, cowardly, or weak man is less valuable to the opposite clan and can’t expect to get a wife, so he can’t be expected to build much of an estate either. Productive men are therefore jealously kept by the opposing tribe.

Recall that some matrilocal societies might have patrilineal descent: the Snake man moves to his Rain wife’s household, but he bequeaths his Snake clan marker and property to his biological children, who are all now Snakes. But this can only be a temporary situation. If patrilineal descent allows Snake children to be born into Rain territory, Snake boys can settle and marry a local Rain girl. Soon, Snake and Rain might combine into a single polity, but this effectively removes them from the matrilocal network. At some point, they must make a hard decision: either remain patrilineal and create a city, or revert back to matrilineal, and intermarry into the larger, matrilocal network, spreading inheritance across it.

If the tribe shifts to patrilocal marriage, then the woman moves to her husband’s household, and the clan marker and inheritance are passed down locally from the man to his biological children. This is the general makeup of ancient Israel, Confucian China, Brahman India, Islamic Arabia, Rome, Greece, and many other Iron Age societies. Typically, it was the eldest son who inherited the bulk of the estate as well as the family priesthood, making him responsible for sacrificing to the family ancestors. If the estate was to be divided between him and his brothers, in Israel, he took a double portion15, and in China, the division of the estate could incite a bitter rivalry with the younger brothers who, prodded by their wives, often demanded an equal portion of the estate. And just like in Rome, when the woman married into the patrilocal household, she was all but disowned from her biological family and adopted into her husband’s—her “affinal”—family. She would mourn her biological family members’ deaths back in her hometown, but she would also mourn her husband’s family members’ deaths. He would mourn her family’s deaths only minimally, if at all.

In a patrilocal society, men typically acquire property through mining, forging, manufacturing, construction, investing, and other similar industries. Property can now be stockpiled thanks to this new inheritance structure and built into one’s estate, or stored nearby almost endlessly, because for the man’s son to inherit, all he must do is stay where he is. The matrilocal man is more concerned with mobility and being a jack-of-all-trades, a valiant man who can raid and hunt, and he hopes to be sought by a woman and snatched up by the neighboring clan, where he will acquire status16. However, the patrilocal man is more concerned with establishing his position and creating an estate, a city, if possible, and possibly a nation. He then attracts a woman, likely pays a high brideprice for her17, and perhaps can get a share of some of her dowry for his own business ventures (if, and only if, she allows him). The incentives are almost the opposite now, like the wealth streams, and they can no longer intermarry. If a matrilocal man were foolish enough to exchange sisters with a patrilocal man in marriage, the patrilocal man’s biological children would receive inheritance from both men, while the matrilocal man’s biological children would get nothing. By intermarrying within a matrilocal society, a patrilocal society can suck it dry or force it to transition to patrilocal.

This only explains what patrilocal marriage is, and there’s no shortage of reading material on the subject. How patrilocal marriage emerges—or, by extension, how a city is formed—is a frontier worth exploring. Below, I’ll examine 3 theories. The first is the mainstream theory. The second two are mine.

1. Big Man Theory of Origin

Lewis Mumford’s The City details how cities emerge due to the works of great men. This “functionalist” line of argument sees culture emerging through people, places, and events. Eric Gans’ theory of the Big Man as founder of agricultural society is similar: one chief or warlord is particularly apt at deferring appetite, allowing himself to acquire a surplus of grain, which makes him a sort of central bank, receiving donations in exchange for regular services. He appoints workers to construct infrastructure around him—a granary, fortification, currency, temple—creating the first cities.

The problem with the Big Man theory is, like those of Jared Diamond and Leonard Shlain, there’s no clear process for going from hunting-gathering to agriculture, from village to city, from matrilocal marriage to patrilocal marriage. It’s assumed that patrilocal civilization—the city—is somehow waiting in the wings, as though such evolution is inevitable. As James Frazer implies, the savages just need time. Some authors will hand-wave the issue away with statements like “when settling made sense, they transitioned to agriculture” or “their culture evolved,” without regard to how catastrophic such changes would be in a matrilocal network. No matter how great the windfall might be, transitioning to patrilocal marriage means deliberately cutting your entire city off from the matrilocal network. And an entire matrilocal network versus a Stone Age city usually ends in the network’s favor.

If the city has iron technology, this changes things. But how does a city acquire iron technology? By being a city. This is the catch-22 nature of “the evolving city” that requires a better explanation. So, before we can accept the Big Man theory, I will present two different mechanisms as catalysts for jumping that gap from the vast matrilocal network to the vertical, patrilocal city: warfare and the tomb city.

2. Warfare

I will now hypothesize two potential ways in which a society within a wide matrilocal network transitions to a narrow, patrilocal one.

The first way is due to the threat of warfare. A patrilocal marriage and inheritance system can incentivize the creation of fortifications to protect the society from outsiders. Perhaps this transition comes before warfare, or follows it. Regardless, just like when Sweden switched all the roads to right-hand drive, the transition requires a hard pivot: yesterday, we were matrilocal, but today we are patrilocal. If the tribe were in enough peril to necessitate this transition, and if it’s large enough to sustain such a pivot and effectively become insular, the shift might be successful in the long term. It seems the Incas made such a pivot, and their empire was ten million strong when the Spanish invaded. They happened to be the only American tribe making bronze thanks to the Peruvian copper and Bolivian tin mines, and it’s difficult to imagine an Inca empire performing these feats if not for its patrilocal inheritance system18.

Making the transition to a patrilocal city system is a huge risk because the city will no longer be able to intermarry with the matrilocal work, putting it at the mercy of the matrilocal network, like a rodent surrounded by fire ants. Without adequate technology, the city will fall. What technology does a city need to withstand the onslaught? It would seem that bronze was the minimum viable product for city defense. To cast bronze, you needed a forge and copper and tin mining. These required the ruling family to be patrilocal to ensure mining rights stayed in the family long enough to exploit the natural resources, hire the artisans to cast the material and forge the weapons, and issue them to the military.

Bronze produced blades far sharper than the stone blade or the wooden spear, and it allowed for chariot warfare. Wood chariots break and tear and are too heavy to allow for more than one user, making them useless in combat. Bronze chariots allowed for 1–3 riders: a driver, an archer, and sometimes a lancer. Chariots could take up the wings while swordsmen took up the center, allowing the Bronze Age army to encircle and defeat the barbarian matrilineal horde.

One problem with bronze is that when it dulls, it must be resharpened, or else it’s melted and recast. Sharpening a bronze blade over time reduces it to a poking stick. Ewart Oakeshott argues in The Archaeology of Weapons that the poking arts—fencing and the like—emerged from this limitation of the Bronze Age. The poking arts are beautiful, but they’re not when you’re trying to enlist the masses. A poking stick in the hands of farmers is no more useful than a sharp stick, since fencing requires years for proficiency. Far better to give them hack-n-slash swords, which were in shorter supply. Bronze also requires tin, but in 1200 B.C., the Philistines attacked the Eastern Mediterranean and cut off the tin supply, making bronze forging impossible.

Robert Drews’ The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe of CA. 1200 B.C. (1993) tells of the sudden downfall of basically every Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age city, which he calls The Catastrophe. The cities had thrived thanks to bronze technology, but with the tin shortage, Hittites and other ironworkers flooded the market with iron weapons. Iron is a superior metal for warfare. It makes for bad chariots, but that doesn’t matter: iron weapons are the hack-n-slash kind, good for putting in the hands of strong but untrained farmers. When an iron sword wore down, the soldier took it to the smith, got a new one, and went on his way. Plus, iron is cheap19. The Naue Type II sword changed the game: Bronze Age chariot armies had no chance against hordes of farmers swinging their swords without regard. In the blink of an eye, the Bronze Age ended20 and the Iron Age was afoot.

Iron was the weapon that defended the city. Whether it was the iron Greek spearhead in the Phalanx, or the Roman Gladius sword, iron in the hands of patrilocal society was the death knell of the matrilocal barbarians. Of course, the barbarians themselves could acquire iron weapons, but without their own forges, repairing them and forging replacements was impossible, putting them at the mercy of the supplier. The city, however, could own and operate mines and forges and enlist metallurgists to cast iron. Later, they could alloy it with carbon to produce steel, producing the razor-sharp, lightweight swords that we see in Japan.

I’ll take a short detour to explain who the “barbarians” were in the context of the city. They were the same as the “gentiles,” the Hebrew goyim or “nations,” the Chinese 鬼人 “ghost man” or the 洋人 “ocean man,” the Greek genos, and the Roman gens. When the history books discuss combating “the barbarian,” this typically refers to a large, matrilocal network outside the city. This network can be nearly infinite in size but diminutive in stature. The barbarians’ inheritance system being incompatible with that of the patrilocal city, the two are constantly at odds. The barbarians strive for hunting, fishing, and agricultural lands under the city’s control, while the city strives to extract tribute from the barbarians. Even though the barbarians had access to iron weapons, the city’s superior iron technology was adequate for fending them off. The book of Joshua details Israel’s decimation of ill-equipped cities in the building of Iron Age Jerusalem. The Manchurian army—not without difficulty—similarly put down the monolithic Taiping Rebellion, reportedly with 20–30 million casualties. The Greeks dominated the Mediterranean with the same means.

Sometimes a patrilocal city would choose not to eradicate the barbarians but assimilate them, as was the case with the Romans adopting the Sabaeans as a secondary group, and the Nabataeans as a third21. The Sabaeans and Nabataeans were patrilocal during this adoption period, but there are indications that, just like the Romans, the original tribal composition of these groups was matrilocal with the typical elder system, and they may have transitioned to patrilocal only after pressure from the Romans. None of this would have been possible without iron, which was not possible without patrilocal marriage.

Warfare acts more as a process that forces the transition from matrilocal to patrilocal, but we’ve yet to pinpoint a specific moment when the transition can occur. The best candidate for such a moment is the ancient tomb, which became a city. To understand this, we must look at China.

3. The Tomb City

Most of my knowledge of Chinese anthropology comes from J. J. M. de Groot’s Religious System of China. Published in six volumes beginning in the late 19th century, de Groot homes in on the religious customs of China just before the monarchy ended in the 1911 Revolution. he was a missionary in Fujian who understood both Mandarin and the local Hokkien dialect, allowing him to corroborate his findings with a litany of primary sources in the original Chinese language.

De Groot’s work touches on many topics, but the one we’re most concerned with involves the origins of the mausolea, or burial places for the dead. It seems de Groot had no idea how insanely important his findings were. He simply described the mausolea in the context of pagan burial practices. De Groot, a Christian, didn’t care what they meant in the Chinese mind or whether they even bore any resemblance to Greek or Roman cities. He simply wrote what he saw, hoping this would aid in evangelizing to the Chinese. Here’s what he writes concerning what happens when a royal personage suddenly dies:

With a view to [the deaths of members of the royal family], the emperors in some cases went so far as to found a walled city in the neighbourhood, and to render it incumbent upon the inhabitants to defend the mausoleum for the protection of which it was built. The first monarch of the House of Han [Gaozu / 高祖, 202 BC] had already done this for his father, although the latter had never been seated on the throne. The ’emperor Gao’, says the San-fu hwang Tu, ‘after having buried his imperial father in the high and level grounds to the north of Lih-yang founded the district city of Wan-nien inside the great walls of Lih-yang, as a place to be intrusted with the care of the fortifications of the mausoleum’. The name he gave to that city is characteristic. It means, ‘Ten thousand Years’, and would, he hoped, ensure to the mausoleum, and consequently bis family, an existence of hundreds of centuries. Of Kao’s own burial place it is on record that ‘to the north of it was the city of Sino, which had been built by (his prime minister) Siao Ho for the defence of the Chang mausoleum. At the outset of the rule of the Han dynasty, the warlike families living to the east of the Passes were transferred to the spot, that they might be entrusted with the care of the fortifications of the monument. Ten thousand families were appointed for the Chang mausoleum and the same number for the Meu mausoleum, these families being placed under the control of the Board of Sacrifices, and not under the local prefect’. Such draconical measures, compelling thousands of people to shift their place of abode, were doubtlessly enforced at the cost of numberless human lives and unheard-of misery.

It seems that seven mausolea were provided in this wise with defenders, for it is stated in the Kwan chung ki that ‘a transference of the people and foundation of a district city has occurred seven times. In the case of the Chang mausoleum and the Meu mausoleum over ten thousand families were transferred, and in each of the other five cases five thousand’. These seven mausolea were probably those of the first seven emperors of the dynasty, it being on record that the eighth emperor, Yuen, mentioned on pages 406 seq., forbade the building of a district city in the neighbourhood of his own burial place, which, in accordance with the prevailing usage of those times, was being laid out in his lifetime.”

De Groot, The Religious System of China, Vol. II, pp. 427-9

In other words, the government employed tens of thousands of people to live at and maintain the royal mausolea, comprised of groundskeepers, gardeners, farmers, herders, priests, and soldiers. Why have soldiers at a mausoleum? Because the dead were traditionally buried with real money—the afterlife is expensive22—and lots of jade, which they believed kept the body from decaying, lengthening the period of its beneficent virtues for the royal family and, by extension, the entire country. Keeping the dead buried with their wealth—including animal and even human sacrifices—kept them happy, which was good for the family and the nation. Therefore, garrisons were erected at the mausolea to prevent grave robberies, turning them into fortified cities.

We have here a potential starting point for patrilocal marriage and the establishment of fortified cities: the immediate need for protection of the dead, basically founding a necropolis. Such necropolises weren’t restricted to royalty; Confucius’ own mausoleum began as a place of mourning but became its own necropolis named 孔 Kǒng after his own name:

As the immediate consequence of the reaction against placing human victims in the graves, dwelling upon tombs is first mentioned in the native books after that reaction had gained a considerable footing. Indeed, the first instance on record dates from the fifth century before our era, and bears reference to Confucius, who, as our readers will see from pp. 807 and 808, was a great antagonist of human immolations.

“Formerly”, thus Mencius relates, “when Confucius had died and the three years of mourning were elapsed, his disciples packed up their luggage, intending to go home. On entering to take leave of Tsze-kung (their fellow disciple), they faced each other and wailed till all of them had lost their voices, and thereupon returned to their several homes. Tsze-kung, however, returned (to the tomb) and built a dwelling within its precincts, where he lived alone for another three years before returning home.” (昔者孔子沒、三年之外門人治任將歸,入揖於子貢、相嚮而哭皆失聲、然後歸。子貢反、 築室於場、獨居三年、然後歸. The Works of Mencius, section 滕文公, I.)

Commentators generally infer from this extract that the disciples had lived on the grave for three years when Tsze-kung, who had conducted the mourning observances as master of ceremonies, settled there once more for the same length of time. In another book of more recent date the same episode is related in the following words:

“The disciples all housed upon the tomb, observing there the ceremonies connected with the mourning of the heart . . . . When twenty-three of the disciples had finished their three years’ mourning for the Sage, some of them still remained on the spot, but others left it, and the only one who dwelt on the tomb for six years was Tsze-kung. Since that time, the disciples and natives of the state of Lu who have established themselves on the grave as if it were their homestead, have increased to over one hundred famillies, and hence that settlement bears the name of the Village of the family Khung.” (弟子皆家于墓、行心喪之禮。..二三子三年喪畢、或留、或去、惟子貢廬於墓六年。自後群弟子及魯人處墓如家者百有餘家、因名其居日孔里焉. The Domestic Discourses of Confucius, chapter 9, §終記解.)

De Groot, The Religious System of China, Vol. II, pp. 795-6

There is evidence of such cities in the Xia and Shang dynasties, c. 2070–1600 BC. Kwang-Chih Chang’s Shang Civilization (1980) explores numerous archaeological Shang sites, revealing that the original Shang cities were indeed built around central mausolea, always those of a king, and frequently also a queen.

If we were to transport ourselves back to the Yellow River valley—a place of rich silt deposits, needing only irrigation to exploit their potential—during the so-called “mythical period” which predated the Xia dynasty, we would likely find ourselves in the midst of matrilocal tribes operating on the same ancient kinship principles as other “barbarians.” These Chinese tribes would have had totem markers and employed intermarriage to defer violence, just like anywhere else23. During the Xia era, various high-class families were able to—or were compelled to—begin the transition to patrilocal marriage and mine copper and tin from Anyang, thereby producing bronze metallurgy as evident in the bronze artifacts of the Erlitou culture. The ruling class names found on these artifacts and oracle bones were always appended with a celestial sign—甲 “wood,” 丙 “fire,” 壬 “water,” etc.—which might have indicated which of the two intermarrying elite clans the leader was from. From this, it seems the ruling families were actually a set of two intermarrying families who remained insular from the surrounding matriloacl network, which nonetheless took up residence around them24.

Just as in Rome and Greece, the tomb of the king—or the legendary city hero—was a site of great spiritual power. The Greek tragedies took place at tombs25. The Roman homes, and the city itself, were founded on or near tombs26. Because ancient tombs were loaded with treasure27, and the Chinese corpse itself exuded beneficial Feng Shui power—and might even be stolen and held ransom. It was therefore a royal prerogative to maintain familial control over these tombs without them going to the dogs. This could only be achieved by transferring ownership to one’s own son, or by creating a two-party system, as in the Xia, which ensured continuous ownership in the male line forever.

Chang’s book details the religious rift between these two ruling families, one more conservative than the other regarding sacrificial practices. Yet, they intermarried in the interest of keeping the tombs in the male line, which was presumably the only way to maintain hegemony in the midst of the matrilocal network, which gradually shifted toward patrilocal marriage to enjoy the benefits of the state and, like in Roman colonies, produce the requisite tribute for the empire in exchange for protection. According to the Shiben (世本), Gǔn (鯀), the father of the Xia founder, Yǔ the Great (大禹)—who also invented the irrigation system that acted as a foundation for agriculture in the Yellow River Valley—reportedly built the first walled towns. All of this confirms what I’ve hypothesized so far: Gun was the first to break from the matrilocal network by establishing an intermarriage pattern between two elite families, creating a patrilocal royal house, with the tomb of his own father being its capital.

But the two-party system in the Chinese royal court inevitably produces cracks in the leadership. As a result, the Shang tribe emerged as the elite patrilocal family, giving rise to the eponymous Shang Dynasty. The Xia tribe didn’t simply go away but continued for generations, and the same happened to the Shang at the onset of the Zhou. All the while, the central patrilocal system was gradually spreading out, “infecting” the surrounding matrilocal barbarians, until practically all of China could be united under a single patrilocal model: Confucianism.

If the first city was a tomb, it could only become a city with patrilocal marriage. This allowed the royal family to maintain hegemony against the barbarians, bolstered with their bronze metallurgy. Although the barbarians were gradually transitioning to patrilocal marriage—allowing their own nobility to ally with royalty, artisans to ally with nobility, and servants to ally with artisans—the ruling dynasty (Zhou) still maintained a monopoly on power thanks to bronze metallurgy, a truly elite weapon form. But as soon as iron metallurgy spread to the general populace, the Zhou court was overrun by hack-n-slashers, followed by a series of wars called the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BC) and the Warring States period (475-221 BC). China’s version of the Catastrophe was the termination of the Zhou dynasty in 221 BC, but the patrilocal system continued to spread throughout China as a means of estate-building, warmaking, and tomb-keeping. This continued until the Manchurians began transitioning China to a bilateral kinship system, which enabled them to utilize firearms more effectively, as described below.

The Real Origins of PLM?

Which was it, wars or tombs, which triggered the transition to PLM? Perhaps it was both, or neither. Building a tomb might have triggered a shift to PLM, war might have triggered the building of a tomb, or PLM might have triggered an uptick in warfare. These phenomena are concurrent in every society, no matter how ancient or modern, and are impossible to place in any definite order.

What we do know is that once the transition to patrilocal marriage occurs—a large tomb becomes a worship site, its ownership is transferred from father to son, a city is built, etc.—the matrilocal network must throw all its resources at destroying it, or else face eventual total conversion. They will use political intrigue, assassinations, embargoes, and raids to target the patrilocal city, which will not—cannot—intermarry with them. If the city is armed with stone or copper, the city will likely fall. Bronze increases their chance of survival, so long as the matrilocal network doesn’t acquire iron. But once the patrilocal city can forge iron, the matrilocal horde is toast. Patrilocal marriage becomes the new operating system, and there is no chance for a rollback.

Rethinking Ancient Kinship

Now that we have a structural understanding of kinship, metallurgy, and the city, we’ll return to the Abraham narrative, which should make more sense now that we’ve parsed the differences between the matrilocal and patrilocal systems, and explore some other ancient phenomena that have remained mysterious until now.

Biblical Kinship – Not As Patrilineal As We Thought?

Abraham and Sarah shared a father, Terah, but they had different (unnamed) mothers, and under the lens of patrilineal descent—the lens of post-Roman Western scholarship—they would be considered siblings and unmarriageable under any ancient law. However, suppose the kinship laws of ancient societies of North and South America, Africa, India, and Australia indicate a pattern. In that case, there’s no way sibling marriage was ever allowed in Canaan28. So, let’s assume that Abraham’s father, Terah, was in a matrilocal, polygamous marriage. One wife birthed Abraham, the other Sarah. Under typical matrilocal law, Abraham and Sarah would have inherited the clan markers from their respective mothers, making them marriageable. In effect, Sarah wasn’t Abraham’s “half-sister,” but his cousin.

But there’s a problematic part of the story where Abraham somehow acquires an Egyptian woman named Hagar, who bears his first son, Ishmael. In the current version of the story, Abraham gives Sarah to Pharaoh under false pretenses, but this may be an edit, and in the original story, Sarah was Abraham’s sister. If he had offered her to Pharaoh, he would have received a sister in exchange, and Hagar the Egyptian fits the bill perfectly. This was a simple reciprocal exchange, an intermarriage that united their families politically. Abraham and Hagar’s son, Ishmael, would inherit the property of Hagar’s brother, Pharaoh himself. And as we see, Ishmael inherits an absolutely insane amount of land: all of Arabia 29.

In Genesis 21, Abraham and Sarah have a miraculous birth, Isaac, whose story, aside from nearly being killed by his father30, is practically a carbon copy of Abraham’s: both of them trick leaders into thinking their wives are their sisters, and both of them covenant with Abimelech over the well of Beersheba. Later, Isaac is almost a parody of an old man, losing his sight and confusing Jacob for Esau because of the fur on his arms. My hunch, unlike Yoreh’s theory that Abraham actually killed Isaac, is that Isaac was a legal fiction created to bridge the gap between Abraham and one of the most seminal patriarchs of the Bible, Jacob.

Jacob’s story is more clearly matrilocal than Abraham’s, since we are privy to many details of his marriage to Leah and Rachel. As per matrilocal custom, he moves to his wives’ estate, where he lives as a hired hand, but after Laban cheats him out of his wages, he heists his wives and children, whom Laban claims ownership over. These children are all crucial patriarchs for tracing Israelite legitimacy: Judah, Levi, Benjamin, and Simeon.

Fast forward to 740 BC when the Assyrians attacked and exiled the northern kingdom of Israel. Judea remained as the sole claimant to Israelite hegemony. The Levites were dispersed in the various cities performing temple duties, Simeon was landlocked and absorbed, and Benjamin was a politically important border tribe. In 597 BC, Babylon attacked Judea, destroyed the First Temple, and exiled the leadership. Nearly 60 years later, Persia sacked Babylon. Ezra the scribe petitioned the Persian king Cyrus to return the exiled leadership to Israel to rebuild the temple. Cyrus approved the plan, and his successors Darius I and Artaxerxes I facilitated the construction project.

Moses claimed to write the first five books of the Bible—the Torah—but the Hebraic grammar and tone, even the details, vary so wildly through the five books that they must have been at least four different documents, written by different authors, all stitched together31. Who stitched these documents together? The best candidate is Ezra. He was in charge of the reconstruction effort. The Torah would have been a kind of constitution that the Israelites needed, which 1. traced the political legitimacy of Judeans to King David, 2. traced the religious legitimacy of the Levites to Aaron, and 3. tied all of it back to Abraham, who had the land deed to Israel.

There were some problems. First, there was no paternal link from Jacob to Abraham, a link that would have concerned the Persian patrilocal leadership. For that, Isaac would have to be created as a legal fiction. Second, Abraham’s matrilineal descent would have given ownership of the holy land to his sister’s—Sarah’s—children. If he had traded her to Pharaoh, then her children would have been Egyptian. It just so happens that Moses and Aaron fit the mold of Sarah’s children perfectly: Moses was a Hebrew raised in Pharaoh’s court, and both, including their sister, had Egyptian names32. The story had to be revised to link Moses and Aaron with Jacob, to tie him back to Abraham, and the entire system rewritten to conform to patrilineal descent customs, which would have given the Israelites the legitimacy to take the holy land back33. The retcon was so successful that we are duped into believing that Abraham lived under a patrilineal system, he married his sister because there were no incest taboos, and he pulled the Sarah con job on Pharaoh just to get some livestock34.

Royal Incest – a Matrilineal Hack

On the topic of Egypt, we find here an anomaly in our kinship survey: royal incest. The Egyptian court reportedly married brothers and sisters together to “keep it in the family.” Frankly, this feels like lazy anthropology. Every family wants to “keep it in the family,” no matter whether it is a watch, an estate, or an entire nation. Why anyone would ever resort to incest, which was tantamount to murder, is the question.

A better explanation is that the royal court—like so many royal families in Africa, as per Totem & Exogamy—was matrilineal. Royal power descended through the female line. Typically, this meant that a king could not pass the crown to his biological son. Instead, his brother or his wife’s nephew or brother normally succeeded him35. The queen’s male offspring often left the city to intermarry into royal families in other cities, where they may never become kings. But royal cities like Thebes and Memphis required fortifications and large temples in the midst of the invasions from Libya, Nubia, and the Sea People. They needed public works projects to survive storms and famines. The copper mines of Ethiopia provided crucial material for bronze forges. Men marrying in from other tribes would not have a vested interest in maintaining these works, so they had to be transferred through the male line to keep them in the family. How, then, could a king pass the throne—and all his property—to his biological son under a matrilocal system?

The simplest way to keep institutions in the family through the matrilineal line is to break the oldest taboo in ancient history: sibling marriage. Breaking this taboo in everyday society was punishable by death because—and this is my own hypothesis—it undermined intermarriage, the simplest means to defer violence between groups. Egyptian royal families got away with incest because royalty and chiefs were often granted temporary, ritual incest privileges as a kind of “vaccine” against incest, intertribal warfare, and infertility. This may have expanded gradually over time until the royal family was allowed ritual incest all year round, perhaps in the interest of year-round benefits, and they became gods themselves in the process. Since gods can commit incest, the royal family can do it too. Royal incest kept property in the family by transferring the crown and inheritance through the queen to her biological children, who also happened to be the king’s biological children, who would remain in the vicinity to maintain the royal court.

But we also have to be cautious about the term “sibling” here. An Egyptian “sister” could have been a fourth cousin on the mother’s side who, by virtue of being of the same clan marker, was still unmarriageable. But a first cousin on the father’s side of a different clan marker was marriageable and preferred, even though they were genetically much closer than maternal fourth cousins. So Egyptian “sibling marriages” may have been the equivalent of cousin marriages by our own biological terminology. And even if their lineages were recorded as having common parents, the records could have been retconned to appear more incestuous and, by extension, more godly.

The Greeks who conquered Egypt even copied this formula. When Alexander’s general Ptolemy Soter took over Egypt, he instituted the same system of sibling marriage for some thirteen generations. But being Greek, royal incest would have been abominable to the Ptolemies. Still, my hunch is these were fictitious “sibling” marriages that appeared incestuous by Egyptian standards, allowing them a triple whammy: 1) legitimacy among their Egyptian subjects, 2) avoiding actual incest, and 3) keeping the royal court in the male line, as per Greek custom.

The Mysterious, Advanced Stone Age City

In general, cities required at least bronze technology to defend against the matrilocal horde, but iron was a more sure-fire defense. That said, there are examples of Stone Age cities, which may have produced relatively advanced architecture, carvings, and tombs. The Easter Island statues are one of the many mysteries of modern archaeology. Same with the 50-foot-tall Fijian Ndakunimba Stones. Graham Hancock, author of Fingerprints of the Gods, claims that these ancient Stone Age cities could not have acquired this technology themselves. It must have come from some outsider.

A simpler, alternative explanation is that these advanced Stone Age cities were early examples of groups transitioning to patrilocal marriage, which kept inheritance local and allowed for fortifications to repel the matrilocal horde. We might assume that in only a few generations, some pretty advanced Stone Age technologies would have emerged thanks to this novel inheritance structure. Trades could be taught directly to one’s biological sons in one’s own language, and some symbolic language might take root. This could be maintained for however many generations until they were overrun by the matrilocal hordes, or a more advanced city overtook them, etc. We need not assume, as Hancock does, that ancient advanced civilizations acquired metallurgy from some strange outsider, or from an angel, as Enoch implies, or from aliens, as so many assume today. A kinship explanation suffices.

Iron

Once patrilocal marriage takes hold within the ancient city, iron forges and mines can be maintained in near-perpetuity. The state might allow matrilocal tribes to preserve their particular inheritance structures. Still, the horde was nonetheless encouraged to convert to patrilocal marriage both to take advantage of the benefits of the city and to provide the requisite tribute to the empire. But the transition from matrilocal to patrilocal would deliver a severe shock to the status quo and could only happen gradually, radiating outward from the capital. Still, there might be holdouts: isolated groups in the highlands, valleys, and other regions might retain their customs for centuries despite economic pressure from the city.

The Iron Age city was practically impervious to the matrilocal horde, unless another Iron Age city attacked it. Such wars were so destructive that it was preferable to engage in the art of politics simply. The way that Commonwealth-era Israel (detailed in the Book of Maccabees) maintained its interests despite the interests of Syrians, Egyptians, and Romans demonstrates how politics had become a high art.

The Iron Age city had one ally, the monastery, but it wasn’t always a cozy relationship.

The Monastery

Buddhist and Christian monasteries established a novel kinship system that was open to both the elite and the downtrodden alike. By simply adhering to the code of the monastery and offering one’s labor, one could acquire a humble room and board with daily meals. But they had to fund their operations somehow. Buddhism originated in India but was eventually overshadowed by the Brahmanical tradition and later by Islam. It was often a scourge to Confucians in China. They resented its messianic promise of eventual happiness in the midst of suffering, feeling that this instilled a malaise that made adherents unwilling to fight for the state. Nonetheless, Buddhism did have an interesting offer for the Chinese empire: the gradual replacement of matrilocal culture with patrilocal culture, something Taoism could never do. It did this with its system of scribes, who often didn’t even understand the original Sanskrit. Many Sanskrit chants were converted awkwardly to Chinese and memorized without knowing their original meaning, which they hand-waved away as though they were magical formulas. The scribes would comb through old Taoist lore and rewrite it with an often shoddy Buddhist prose. Animal totems were no longer clan markers that passed through the mother, but martial symbols that one inherited through the father. In this way, Buddhism could defang matrilineal totemism, and we believe to this day that the various martial arts—even duck martial arts!—were pioneered by patriarchs observing animal combat. But this was no mere goodwill gesture to the state: the Buddhist monastery had an interest in converting to the patrilocal system to fund its system of temples and lands, which could be bequeathed from the local populace, but in far greater amounts if the populace was engaged in patrilocal marriage.

Buddhism came to Japan through China, and there it was more successful at bonding with the emperor, which allowed it to acquire inordinate amounts of land tax-free, with which it could sell produce and fund temple construction. The Japanese Buddhist scribal retcon job against the matrilocal horde was presumably more successful, despite the Japanese language being now two degrees of separation from Sanskrit. And yet it was unbelievably sloppy. Their stories have vestiges of Shinto animism and matrilocal totems, but their resolutions are often shoddy, like a Buddhist scribe was getting too comfortable with the whiteout. Read this one:

Once upon a time there was a local official who was covetous and greedy. He got money by raising silk-worms which it was his wife’s duty to feed. Once she failed to rear them successfully and the husband scolded her and turned her out of doors. Abandoned by the husband and left with only one silk-worm, she lavished all her care upon it. One day the precious worm, upon which her hope of a living depended, was eaten by her dog. She thought at first of killing the dog, so furious was her anger, but she reflected that the worm could not thus be restored, and that the dog, after all, was her only companion. She was quite at a loss how to sustain life, but she calmed her troubled mind by thinking of Buddha’s teaching of love and of

karma.One day her dog somehow had his nose injured. The woman found a white thread protruding from the wound and tried to pull it out. The thread came out endlessly until she had got hundreds of reels of fine silk thread. Then the dog died. She buried the animal under a mulberry-tree, praising Buddha for the grace which he had shown her through the dog. The tree grew swiftly and silk-worms appeared among the leaves. The silk which they produced proved to be the best in the country, and the woman sold it all to the Imperial court. Her former husband coming to learn of this, repented of his greed and cruelty. He rejoined his wife and thenceforth they lived in peace and prosperity.

Masaharu Anesaki, The Mythology of All Races, Vol. VIII (Japan), p. 322

Buddha as deus ex machina crops up often in Japanese myth, not because the myth is of the simple Buddhist kind, but because Buddhism in Japan, like in China, had a propaganda arm which could convert old matrilocal totem groups to the state’s patrilocal system, allowing it to engage in heftier statecraft: enabling agricultural and other public works projects, amassing armies, etc. And the effort was even more successful in Japan, where Buddhism has since thrived, much thanks to a patrilocal inheritance structure that allowed the transfer of massive, wealthy estates to the church through clever manipulation36.

The story of the Catholic Church is similar and better documented thanks to Jack Goody. The Gospels and the Epistles outlined a new kind of spiritual kinship divorced from worldly ties. “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his father, mother, wife, children, brothers, and sisters, as well as his own life, he can’t be my disciple,” said Jesus in Luke 14:26. In Matthew 10:34-39 Jesus states, “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace but a sword.” The implication was that traditional families—patrilocal and matrilocal alike—would be ripped apart by the Gospels.

When Constantine made Christianity the state religion, the Christian bureaucracy introduced various inheritance reforms in addition to the old Roman patrilocal marriage structure. Divorce was outlawed, and remarriage was staunchly discouraged, which often meant childless widows were left with large estates with no heirs. A sly priest could then sweep in and, offering social or spiritual promises, could convince the widow to will the estate to the Church on her death. Adoption, while not outlawed, was discouraged, which helped prevent estates from going to childless couples, going instead to the Church. In its most egregious stage, marriage was limited to cousins of the sixth generation, which forced men in small towns to leave the family estate to seek brides of more distant blood, again leaving the estate up for grabs by the Church. All of this—including the ban on the levirate—was couched under “Biblical morals” when, in fact, they flatly contradicted Biblical kinship laws, which allowed for cousin marriage, the levirate, remarriage, divorce, and adoption. So long as nobody was actually reading the Bible—and one couldn’t before the printing press—nobody was the wiser that these kinship reforms were driving untold wealth toward the church37. This is not to attack the Church; the wealth was often used for good: orphanages, caring for widows and the elderly, and the funding of sciences at universities. Much good came out of this wealth transfer, as did much bad. This essay only examines it as a system of kinship.

The Iron Age City also had a severe thorn in its side: horseman culture.

Horsemen